Last Day

Despite my best efforts, today is the day I have to leave McMurdo and return to the real world. It's been an unbelievable experience so far, but after three short-yet-long weeks on the ice, it's time to head back home. In every respect, this trip has been a success, though none of the success came quite as easily as we'd hoped. Just about everything seems to take longer and require more more effort, elbow grease, debugging, and loss of sleep than I expect going into it. Even though I've come to expect incorrect expectations, setting that twiddle factor seems to be one of the hardest but most important skills that one can acquire through experience.

Skiing after Yeti on the endurance test.

The night before last, I had the opportunity to speak to Roberta Palmiotto's class of 9th and 10th graders, who had a number of great questions about Yeti and life in Antarctica. Thanks to Roberta and the whole class, it was quite the treat to talk to them, and hopefully a few of them will consider joining the next generation of polar roboticists. It's clear that there's unbounded potential for robots in extreme environemnts, but one of the constraints on the Yeti project has been getting the right combination of people and skills to design, build, program, debug, test, and deploy the robot. This is definitely the coolest job I can imagine, aside from my work at PSI, which is essentially the same thing but more secret and indoors. One of the major next steps is finding the right people to carry the project forward, though I'll have to leave that to Professor Ray and Jim. They recently received word that their proposal to extend the 'Cool Robot' project was funded, which is really exciting news.

I've been told that Halloween is the biggest and most significant holiday down here at McMurdo, and everyone pulls out all of the stops with creative costumes. I was scheduled to fly out about 4 hours before the Halloween celebrations began, but every single flight in the last two weeks has been delayed, and several people have spent another full week just waiting to take off. Hoping I would get a 12 hour delay and fly the next morning, I eagerly waited and waited until it became clear that the flight was not delayed and I really would have to leave. To add insult to insult, I'm the ONLY passenger on this flight from McMurdo, joining one Medical evacuee from the South Pole. I'm not sure what the cost per hour to operate a C-17 'Globemaster' is, but I'm pretty sure that my return trip cost is in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. I was expecting to be crammed in with pallets of cargo but I'm sitting with the flight crew and an entirely empty plane. I'm guessing that the plane delivered a bunch of cargo on the way in, but it's still quite the experience to get a private flight on a $237 million dollar air force plane (some sources say only $191 million).

One last look at Mt. Erebus, outgassing volcanic steam and vapors on a perfect afternoon.

I got to ride up in the cockpit for a while, and the pilots from the National Air Guard gave me a walkthrough and answered some questions about the plane. I thought that our drive in the Case tractor, at 3 gallons per mile, was pretty poor fuel efficiency, but that's NOTHING compared to this beast. This trip to take me off the ice will burn 180,000 lbs of fuel, or approximately 35,000 gallons. I felt bad about commuting to work in a civic every day, but apparently this one trip alone will release 270 TONS of CO2, putting me at 67.5 times the average worldwide annual CO2 emissions per person for this one flight alone. That sounds unbelievable, but it's based on a burn rate of 7,000 gallons per hour, and 3 pounds of CO2 output for every pound of jet fuel burned (oxygen atoms are heavy...). The plane was bringing food and supplies down to McMurdo, so I'm just catching a ride on the way home, but it definitely doesn't give me warm fuzzies for being a good global citizen. I just found out that there were supposed to be another nine people on this flight, but somehow ALL NINE OTHER PEOPLE convinced the NSF that they had a good reason to stay for Halloween, and I was the only one without a good enough excuse :(

The sadly empty inside of my private C-17.

On Wednesday morning, we had several hours to perform the last test on Yeti. Since everything else worked out well, we wanted to show that we could program an autonomous run in which Yeti would traverse out across the ice to a predetermined point, then execute a rosette pattern over a simulated crevasse location to collect radar data from different approach angles to the crevasse. This should have been trivially simple, but required scaling up the number of waypoints we sent Yeti from 10 to 150. After finally getting everything set up, we sent Yeti out to execute a 1 mile run with two rosette pattern searches along the way. It perfectly executed the first, then stopped and waited for instructions. With 10 minutes remaining before we had to crate Yeti up to ship it back to NH, we had to stop the test and bring it home. I'm pretty sure that this is a trivially simple bug that caused Yeti to stop early. This is a capability we can easily demonstrate back in New Hampshire and an add-on to our original goals, but it was still a little frustrating that it didn't work without modification.

The view out the window on the way home.

I'll continue writing until I get home, on Sunday the 7th. I'll be holed up in a library in New Zealand furiously working away on projects for PSI until then. I need to thank everyone who helped make this trip possible. I'd principally like to thank Jim Lever and Professor Ray for creating this opportunity which began in 2007, and sticking with the project since that time to help in every possible way. Without their advice, guidance, and support, we'd never have made it off the drawing board. Our Greenland deployment, and subsequently this trip, would not have been possible without the sponsorship and support from Ken Corcoran and the folks at Geophysical Survey Systems Incorporated. Thanks also to my 190/290 project teammates who worked insane hours through 2007-2008 to build Yeti in the first place, and Chris, Taro, and Max who did the groundbreaking and exhaustively thorough initial conceptual chassis design. I wonder if they ever expected to see it get this far, I certainly have been pleasantly surprised. Finally, thanks to everyone else at Thayer who helped us along the way. Thanks to all of the support staff at McMurdo and with the USAP. They outnumber the scientists by 10:1 and work 6-days a week, 10 hours a day. Many of them come to Antarctica for the unique experience, but have to earn the right to be here by working insanely hard, many with irregularly rotating night shifts and without weekends. I also need to thank NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab for the initial education grant that funded us to build the robot, and the NSF for their continued support of our field operations in Greenland and Antarctica.

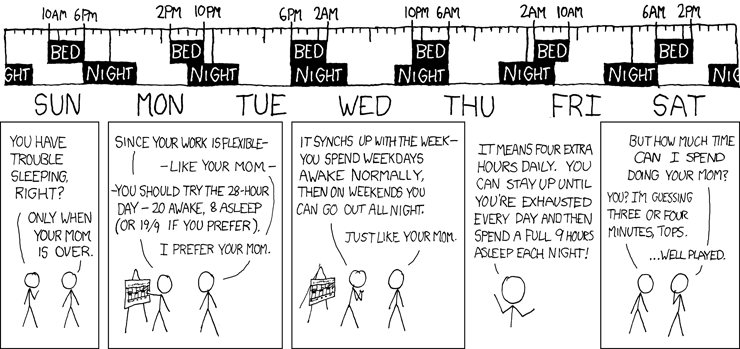

Lastly, but extremely importantly, I'd like to thank everyone at PSI for making it possible for me to take a few weeks off to be here. Initially it looked as though the scheduling would work out a lot better than it did in reality, and I need to thank Brian, Jay, Emily, Charlie, Pete, Peter, Marty, Jim, and especially Dave for picking up some of the slack while I'm gone. Now that I'm back, it'll be a few weeks of the 6-day 28-hour schedule to get caught up and prove my worth again :).